I wonder if there’s a secret room within the headquarters of our various state and territory fisheries departments where the powers-that-be lock away small groups of boffins and bureaucrats, tasked with dreaming up the most unsustainable fishing practices their minds can possibly conjure? I’m being facetious of course, but seriously, sometimes you do have to wonder.

The “glory days” of the south east trawl fishery, when fortunes were made and dynasties built. Of course, they didn’t last.

Don’t worry, I get it. The world needs protein, and some of it must come from the sea. The economy needs jobs, and some of those need to be in commercial fisheries. Consumers want to be able to buy fish, and a lot of it must be harvested from the wild. But there also needs to be a balance, and a cautious eye to the future and longer-term sustainability.

I often think back to the days of the NSW fisheries research vessel Kapala. This sturdy old trawler plied the waters of my home state right through the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, dragging her nets, sampling what lived below, and providing the vital information necessary to create and grow entirely new commercial fisheries that hadn’t previously existed.

The fisheries research vessel Kapala pioneered new fisheries off the south eastern seaboard. A piscatorial gold rush followed.

In particular, the Kapala’s efforts uncovered massive stocks of redfish (nannygai) and gemfish along the continental slope off the NSW south coast, along with smaller but still very significant populations of jackass morwong, ling, blue grenadier, mirror dory, tiger flathead and several other important commercial species.

With energetic government encouragement, tuna poling boats were rapidly converted into trawlers (the tuna fishery was in decline, so the timing seemed fortuitous). An entirely new industry was born. Fortunes were made. Fishing dynasties were built. Port towns prospered along the coastline adjacent to what became known as the South East Trawl Fishery. But sadly, it was all a short to medium term illusion, built on a foundation of shifting sand, and none of it was truly sustainable.

Massive hauls of nannygai or redfish were made in the early days of this fishery, but over time the stocks collapsed. They’ve never fully recovered.

Interestingly, in 1996/97 the Kapala returned to these waters to re-assess them: using identical gear and methods to those she’d employed to reveal the existence of these trawling grounds 20 years earlier, back in 1976/77. What she found on her return was sobering. The overall catch had shrunk to less than a third of its original size, while the commercially viable part of that haul was now just 26% of what it had been two decades earlier… and declining.*

For some important target species, things were far worse than that. The vast redfish (nannygai) schools of the mid-’70s were almost gone, and those nannygai that were left were mostly tiny. The same was true of several other varieties. In 1976/77, catch rates of jackass morwong (marketed as “sea bream”) had been as high as 800 kilos per hour. In 1996/97, only seven morwong were caught during the entire survey period… Not seven tons. Not seven kilos per hour. Seven fish. Full stop. The boom was well and truly over. The fishery had effectively crashed. It has never really come back.

Jackass morwong went from abundance to relative scarcity in just a couple of decades. Like nannygai, their stocks have never really recovered.

You’d think we might have learnt a few things from cautionary tales like these. But we haven’t. We keep right on doing it. Or rather, our so-called fisheries “managers” (and I use that term loosely) keep doing it. Orange roughies. Tuna. Pilchards. Southern school sharks. It’s a continuing sorry cycle of discovery, encouragement to participate, boom times, over-exploitation and bust, typically followed by tighter and tighter restrictions that are often too little and too late, but still enough to destroy livelihoods and impact communities.

I once had a fisheries manager try to explain the declining orange roughie fishery to me in mining terms. To paraphrase, he basically said “you can’t really manage a stock like that because they grow so incredibly slowly and live for so long… you’re better off just to strip mine them and hope you miss enough so that the population doesn’t disappear”… Nice.

Now the crosshairs are fixed firmly on iconic sportfish like the golden trevally and Indo-Pacific permit or snub-nosed dart.

It pains me to say it, but it’s happening all over again, this time with Fisheries Queensland appearing hell bent on introducing something called “tunnel netting” to the inshore tidal flats of the Sunshine State’s tropical and sub-tropical waters.

As many readers will know, extensive net-free zones have been introduced along significant stretches of the Queensland coast, and fish populations have rebounded as a result — along with tourism and spending by recreational fishers. The world-class barramundi and threadfin salmon fishery now thriving in the lower Fitzroy River at Rockhampton is a classic example of this recovery process.

Threadfin and barra numbers have rebounded spectacularly in the net-free zones… So spectacularly that the netters and their friends in QLD Fisheries are now seeking new ways to decimate their stocks!

But just as nature abhors a vacuum, it appears that commercial fishers, the seafood industry and the government departments doing their bidding abhor the idea of so many more fish swimming around out there in the wild, rather than lying glassy-eyed on fish shop shelves, or packed into foam boxes heading for overseas markets. They seem to view live, wild fish as a “wasted resource”. Something must be done about them!

Their latest brilliant scheme is to find a harvesting method to replace large scale mesh or gill netting — a practice that’s on the nose with the general public, as much for the number of dugongs and turtles it drowns as any other reason. The answer they’ve come up with and are now extensively “trialling” (with taxpayer funding, I assume) is tunnel netting.

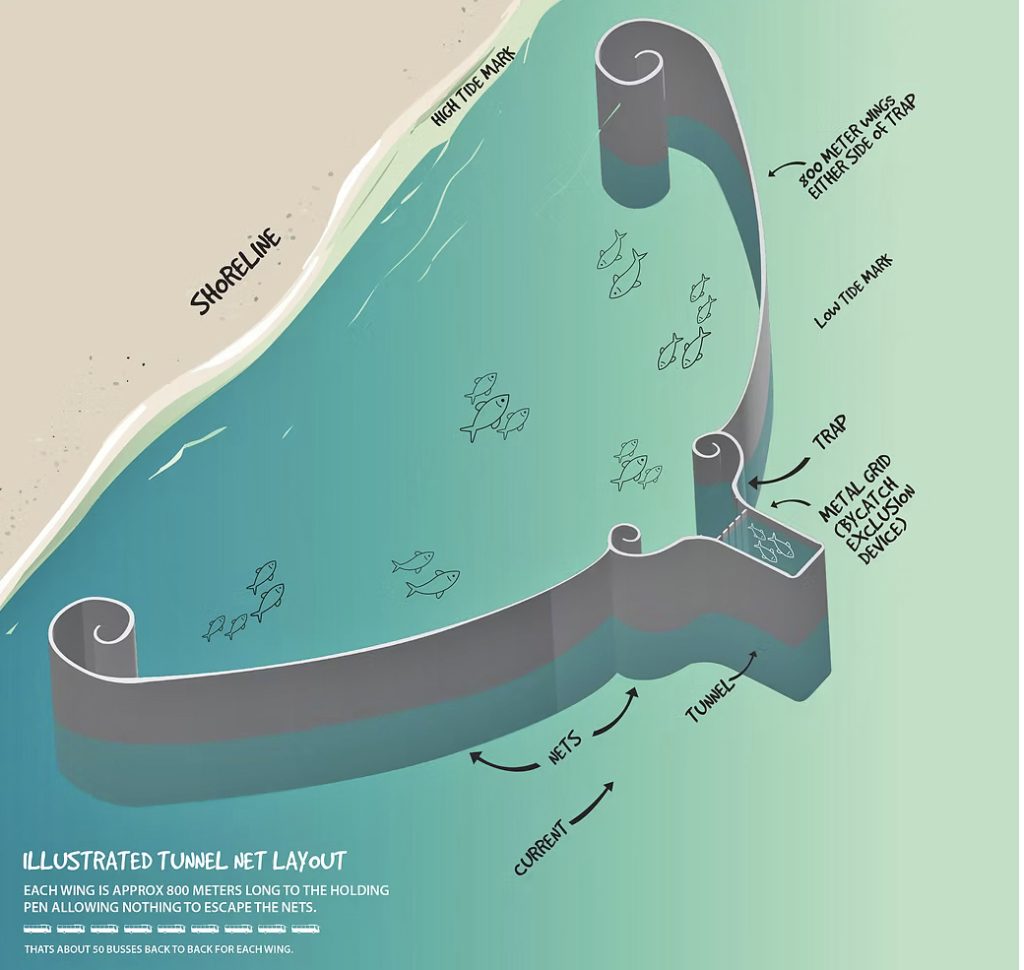

This is how tunnel nets work. Up to 1.6km wide, they funnel everything that swims into a central “killing cage”. (Image courtesy of The Inshore Flats Project)

On paper and in Fisheries Queensland’s expertly spun promotional videos, tunnel nets look like the perfect replacement for those nasty old gill nets. In fact, the cleverly massaged propaganda on tunnel nets was so slick that the ABC’s Landline program picked it up and ran it. I watched the segment and thought: “Yes, that looks okay. Much better than mesh nets!” I’m sure I wasn’t alone. But we were duped.

In reality, the “trials” of these nets have quickly shown them to be super-efficient killing machines. According to multiple observers with skin in the game and whose word I trust, the tidal flats where these “trials” have taken place were virtually devoid of life for days and even weeks after a single deployment of these catch-all set-ups. Most still haven’t recovered.

Unwanted fish can supposedly be released from the tunnel net’s “cage”, but over-crowding and physical injuries in the enclosed space likely result in high mortalities. (Image courtesy of The Inshore Flats Project)

The “wings” of these nets are up to 800 metres in length, giving a total spread of 1.6 kilometres. They use the falling tide to effectively funnel everything that’s too large to pass through the mesh into a “cage” structure. In theory, by-catch can be sorted here and released alive, but in practice, lots of these “discards” were reported to be either dead or in very poor shape, making them highly susceptible to predation by the seabirds, sharks and crocodiles these activities inevitably attract.

The “trials” alone of these nets reportedly caught 30,000 fish, representing 50 species. The average catch per set exceeded 1,800 fish weighing more than 770 kilos, but one shot caught over 6,000 fish. High on the list of species taken in big numbers during the trials have been iconic, keenly-sought sportfish such as golden trevally, permit (snub-nosed dart) and queenfish. These species have relatively low market prices, but are incredibly valuable to recreational anglers, who spend big dollars pursuing them and then typically release most of those they do land.

Yes, the by-catch can sometimes be released… straight into the clutches of any waiting predators such as pelicans, sharks and crocodiles! (Image courtesy of The Inshore Flats Project)

Don’t take my word for any of this. Go to The Inshore Flats Project’s very professional and well-researched website and read all the background. Sign up for their newsletter, talk to your local member, and when The Inshore Flats Project launches a petition, please add your name to it. As well as the links embedded in this paragraph, you’ll find a button below that’ll take you straight to The Inshore Flats Project.

We have a big and very important fight on our hands with this one. What’s at stake is one of our country’s blue ribbon inshore and light tackle sport fisheries — a fishery that currently generates significant economic and social benefit with minimal environmental impact. Do we really want to trade all that off to allow a relative handful of operators to briefly make big bucks while driving another publicly-owned natural resource over a cliff?

* Statistical data from FRDC Project No. 96/139 report, issued December, 1997. ISSN 1440-3544

Until next time, Tight Lines.

![]()

Steve (Starlo) Starling is an Australian sports fishing writer and television personality who has appeared in many of Rex Hunt’s Fishing Adventure programs on the Seven Network.

He has published twenty books on the subject of angling, as well as thousands of magazine articles.

Starlo has scripted and presented many instructional videos and DVDs, and been a Researcher and on-screen presenter for a number of Australian angling and outdoor television programs.

Follow Starlo Gets Reel on Youtube for some of the best, educational and most entertaining fishing viewing on-line.

Click on the banner below for a direct link to the Channel.