As three sailors from the Australian Navy prepared for a unique mission on Sydney Harbour, they were first checked for unusual contraband: bananas.

The “sea trial” they were about to embark on revolves around the science linking gut microbiology to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

But the bananas are banned for purely superstitious reasons.

The ban stems from the 1700s, when many of the ships lost while sailing between Spain and the Caribbean just happened to have a cargo of bananas.

Bunches also often carried deadly spiders, didn’t transport well and to this day fishermen swear they never catch anything when bananas are on board.

So just in case, two of the offending yellow fruits were pulled from bags and handed over for immediate consumption.

One belonged to Adrian “Smiley” Whitby, a 46-year-old former aircraft maintenance engineer with the Australian Navy who has done three major operational deployments to the Middle East.

Adrian felt like his life had been jinxed for no obvious reason.

In 2016, he was diagnosed with an extremely aggressive form of prostate cancer and underwent major surgery to remove the tumours.

He also developed depression, from which he has been struggling to emerge ever since.

A gut instinct for what’s wrong

Adrian is taking part in a sailing day organised by the charity Soldier On, one of a range of recreational activities known to improve mood and mental health.

He’s passionate about the healing powers of the sea, but this day is about more than the physical act of crewing the boat.

A mood-lifting day on Sydney Harbour on the 40-foot yacht Isa Lei (a sad Fijian farewell song).(ABC News: Michael Troy)

Adrian is keen to learn more about the needs of the invisible crew inside his own body, known as the microbiome.

US Navy researchers recently published a study on the body’s “bacterial engine room” suggesting gut microbes may hold the key to preventing PTSD and mood disorders such as anxiety and depression.

“I firmly believe the gut is a key piece of the puzzle to PTSD,” said one of the authors, Dr Marti Jett, a Chief Scientist with the US Army.

“After a trauma, there is clear evidence the makeup of the gut bacteria changes and if unhealthy eating habits develop it could lead to a rapid downward spiral.

“Firstly, there is the likely course of wakefulness, lack of sleep, even nightmares.

“Then other PTSD features will be added: uncontrolled anger, hostility, family issues, [not] holding a job successfully, pre-diabetes and addiction.”

Taking the growing body of evidence out of the lab and into the real world though has proved a real challenge for scientists around the world.

Dr Jett said the sea trial is a very interesting, practical way to help people understand the importance of their gut health.

Powering up the ‘crew within’

Feeding the “crew within”, anchored near Manly, Sydney Harbour.(ABC News: Michael Troy)

Nicole Rothacker, the ship manager for the RAN’s training ship Young Endeavour, tucks into a feed similar to what crew of the original Endeavour ate.(ABC News: Michael Troy)

“I always thought I was missing a piece of the puzzle to what was going wrong for me,” said Adrian.

His rates his mood a five out of 10 when he gets on board.

But that starts to immediately improve as the 12-metre yacht Isa Lei — donated for the day by skipper John Webber — sails into a 15-knot southerly and some gut-friendly foods are brought on deck.

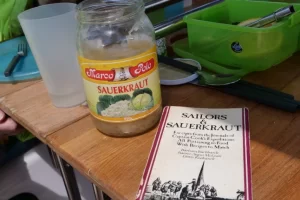

A taster box is handed round full of sauerkraut, chopped turnips, carrots, limes, celery, cherry tomatoes, fresh figs, breadfruit, cheese, olives and an English dip resembling hummus called pease pudding.

“It’s nearly all the things I don’t like,” said Dee, as the others encouraged her to have a try.

Her objections are nothing new. But sailors have long known of the link between food and physical health, even if its effect on mental health is only now being understood.

In 1769, the legendary explorer Captain James Cook faced the same response from fussy sailors who were unwilling to try “exotic” foods, content to stick with dried beef, salted pork and ship’s biscuits.

It was the age of scurvy, where millions had lost their lives to the horrendous disease.

Lieutenant (as was his rank then) Cook was determined to persuade the 95 men onboard HMS Endeavour to take part in his food-as-medicine experiment as a matter of life or death.

“The sour Kraut the men at first would not eat until I put in practice a method I never once knew to fail with seamen, and this was to have some of it dress’d every day for the Cabbin table and permitted all the officers to make use of it. The moment they see their superiors set a value upon it, it becomes the finest stuff in the world and the inventer of an honest fellow.

James Cook’s journal, Tahiti, Thursday 13 April 1769

Cook had no way of knowing it at the time, but he was effectively feeding the “microbial crew” within his crew.

He also enlisted the help of friendly sea-borne bacteria and viruses known as phages to ferment and transform poisonous water supplies into safe-to-drink beer, which Cook also believed would prevent scurvy.

The Endeavour was loaded with large quantities of wort and malt to open-ferment beer in barrels on deck with each crew member allocated a gallon a day, which may have left them with a hangover but kept them alive.

Today the crew is offered the non-alcoholic fermented brew kombucha.

Fermented foods and drinks are like a catalyst for the complex communities of microbes in the gut, according to Australia’s leading expert on nutritional psychiatry, Professor Felice Jacka at Deakin University’s Food and Mood Centre.

“Vinegars such as balsamic and apple cider appear to be very beneficial to the gut, as are the fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha, tempeh and other such traditional foods,” said Dr Jacka.

An old sailor’s guide to essential eating at sea.

Back on an even keel

Cook’s other secret weapon against scurvy was the fresh produce he picked up on the way, which his one-armed cook, John Thompson, skilfully mixed with supplies onboard.

His recipes are detailed in a little-known Canadian book from the 1970s titled “Sailors and Sauerkraut”.

After a few hours sailing Sydney Harbour, tummies are grumbling as some of the recipes are read out.

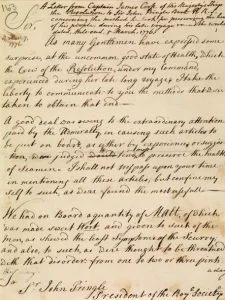

Captain James Cook’s letter to the President of the Royal Society of London in 1776 outlining his methods to prevent scurvy.(Supplied)

“Roast pork in imitation of the Polynesian manner”, “herring with greens”, “sauerkraut roll and pickle with pork”, were just a few of the surprise gourmet offerings.

The anchor was dropped and a lunch straight from 1770 was served.

A large pork sausage with sauerkraut, greens and pickle on flat bread, followed by fruit (from Tahiti, we pretend), with rhubarb and pearl barley pudding with chocolate on top.

The high-fibre feast provides plenty of resistant starches — as they are described by the CSIRO — that are not digested in the small intestine and make it to the large intestine or bowel to be broken down by the hungry microbes that live there.

At the end of the day, Adrian estimates his mood is up to a nine out of 10, as he could feel the benefit of making sure his “gut crew” were also well fed.

“Sailing and being on the water was energising for the soul,” he said.

“It is hard to trade out a single part of the day as the best part, but it would probably be learning about the food and methods that Cook employed to maintain the health and welfare of his crew. And that his methods are still available to us today.”

A gutsy effort by a remarkable explorer and mariner

Captain James Cook’s breakthrough in preventing scurvy was undoubtedly one of his proudest achievements.

The advances made in ensuring the health of those on board the Endeavour during Cook’s first Pacific voyage had been overshadowed by the terrible death of 21 of his crew caused by fevers contracted at Batavia (Jakarta) after the ship left Australian waters.

On his second voyage in HMS Resolute, Cook was able to perfect the methods he had experimented with on the first, and despite months spent circumnavigating the globe in Antarctic waters, out of sight of land and lacking fresh supplies of fruit and vegetables, none of his crew died of scurvy.

In 1776 he presented his work to the leading scientific body of the time, The Royal Society of London, and was awarded the Copley Medal.

The Method taken for preserving the Health of the Crew of His Majesty’s Ship HMS Resolute during her late Voyage round the World.

— Close attention to cleanliness on board

— Procuring fresh food whenever possible

— Carrying and using a variety of the substances with known or suspected antiscorbutic properties such as Sauerkraut, Portable broth (a soup, prepared from cattle offal and flavoured with salt and vegetables, then evaporated to hard cakes) Salep or saloop (a powder made from dried orchid roots), mustard, marmalade of carrots (carrot juice evaporated to the consistency of treacle), Rob of lemon and orange (their juice evaporated to a syrup), Malt (partly germinated then dried barley), and inspissated juice of wort or beer.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Volume 66, 1776.

James Cook may have also personally experienced the downside of a dysfunctional microbiome and its link to PTSD.

His gut harmony first hit a sour note during his third voyage around the world, which started in July 1776.

His journals record that after a few months at sea he had “bilious colic” and developed chronic constipation, which he tried desperately to treat himself, with little success.

Lieutenant James Cook was awarded the Copley Medal for his work on maintaining the health of his crew.(AAP: Royal Society)

The HM Bark Endeavour replica.(Supplied)

Up until then Cook had been described as a “humane and gentle circumnavigator with a refreshingly civilised attitude toward the men who served under him and the natives he met”.

The “other” James Cook, as he was sometimes referred to by his crew in 1779, had lost his burning curiosity and had become cruel, irritable and profane.

It’s said he constantly delayed and vacillated from one plan to another and tempted fate repeatedly with foolhardy acts.

Ultimately, this recklessness led to his death in a melee he provoked with Hawaiian warriors and from which he might easily have escaped, had he made any effort to flee his attackers.

Michael Troy is a freelance journalist, sailor, guest speaker and raconteur. Apart from his superior skills in the media, he is also an expert in International Politics specialising in the Middle East, having graduated with a High Distinction in both subjects.

As a guest speaker, he will enthral you speaking about Epigenetics, the microbiome and dysbiotic drift. He says, “Science that I love to explain while sailing as the sea is the place ‘from whence we came’. However, I have catered for landlubbers with a simulated voyage through space and time to reach Elysia, the legendary resting place of worthy mortals”.

Michael Troy will be known to many, as a Senior Reporter / Producer for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). You can connect with Michael through LinkedIn.