Back in 2016 Danny Casey took us through the evolution of Japanese outboards and how they turned the market on its ear. From the first cautious attempts at two strokes to the advanced four strokes of today, they rewrote the rules on outboard engine technology. Whilst circumstances and brand line-ups have since changed considerably, it is good to read his insights from 7 years ago.

In the late 1950s, an executive from a fledgling Japanese company was doing reconnaissance at a trade fair in Europe in an effort to gauge what sort of competition would be faced by Japan, still trying to forge its way in the world as part of the long, arduous rebuilding programme that followed the Second World War. Seeing nothing of note or quality on display from his home nation, the Japanese executive repaired disconsolately to his hotel bar and ordered a cocktail of some sort. When the barman appeared with the drink, he chirpily mentioned, by way of airy small talk, that the cocktail umbrella plonked in the middle of the executive’s drink was made in Japan.

Rather than feel the rousing stirrings of national pride, the executive was acutely embarrassed – at this trade fair showcasing the pinnacle of international technology and innovation, all that could be attributed to Japan was a tacky, flimsy cocktail umbrella. The executive promised himself that, if he had anything to do with it, his small company, and Japan, would soon make an immense impression on the world. His name was Akio Morita and his fledgling company, a manufacturer of electronics, was called Sony. While Morita plays no direct part in what follows, his spirit, tenacious foresight and fortitude must almost certainly have been adopted by those companies who do.

SECOND BEST AT BEST

About forty years ago, growing up in Ireland, I went with my father, who used to buy and sell boats and outboards, to look at a supposedly cheap twin-bilge-keel sailing boat which also had an outboard of some description. In those days I knew little about sailing boats and didn’t much care for them, but my father reasoned that if it were cheap enough, there was profit in it.

We met the owner at a nearby jetty, where he had beached the boat on its keels so we could have a look around it. Whilst my father engaged the owner, I made a beeline for the strange-looking outboard, which had a grey leg, a yellow top cowling and rather bulky, cumbersome styling. The tiller handle, swathed in insulating tape as a substitute for a lost throttle grip, lay limp against the transom well. I pushed it up but it plummeted, unchecked, back down and thwacked the boat like a barrier falling on a car roof. At this, the owner suddenly stopped in mid-sentence with my father then directed his somewhat panicked gaze at me and stuttered: “Ah…yyessss, I…I…I was coming to that. It did have a proper (!) outboard on it – a 6hp Johnson – but it fell into the water and I never got it fixed. I bought that cheap as I had to have something to push the boat. Look, if it helps, I could drop fifty quid but that’s the best I can do.”

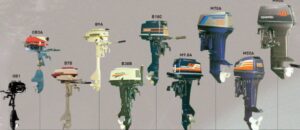

The source of the owner’s severe embarrassment was an early, rather tatty Japanese outboard motor – a Yamaha P7A. As a deal-clincher, it was not a drawcard but a decided drawback. Much as it mortifies me now, I and my father also agreed. But what was lost on all three of us was that the P7A was by then at least 12 years old and still ran faultlessly (albeit a bit noisy and “thrashy” on account of being air-cooled with a single cylinder). However, the owner’s apologies and desperate price drop reflected the thinking prevalent then. Different times indeed and no one could have imagined that the manufacturer of that boxy, rudimentary, rattly P7A would go on to be the world’s largest manufacturer of outboard motors or that other Japanese companies could also embrace the concept so enthusiastically and proficiently.

HOW DID THE MIRACLE HAPPEN?

When the immediate post-war period is discussed, everyone gravitates towards the rebuilding of Germany after the Nazis and how the four major Allied powers each oversaw different facets of the rebirth and collectively got the foundries, factories, shipyards and auto factories back on track. But whereas Germany had an abundance of raw materials like iron ore, coal and steel, the other vanquished nation, Japan, had nothing – not to mention that it was (and still is) the only nation ever to have experienced nuclear attack. While the Germans had the concerted efforts of the Axis powers overseeing their recovery, Japan had primarily only the Americans, and really one key figure, General Douglas Macarthur who, with his staff, was essentially charged with rebuilding the nation. There is a story, maybe apocryphal, that Macarthur grew so tired of the problems involved in even trying to place a phone call (so damaged was Japan’s infrastructure) that he needed the help of a professional.

And so arrived William Edwards Deming. Deming was an engineer, a professor and also (but this was before such an occupation became the term of disgust and distaste it is today) a management consultant. But his methods, practices and achievements spoke for themselves. Deming advised the nascent Japanese industrialists on quality, productivity and manufacturing techniques which basically mirrored the practices of the United States and the Japanese, excellent and attentive students, hungry and eager to restart the shattered economy, embraced these policies to the letter. And so was born the “miracle” of modern Japan – except that there was nothing particularly miraculous about it. Any Japanese factory or office in the post-war period adopted virtually the same practices, layout and utilisation of facilities as, say, Ford, GM, Chrysler, US Steel or IBM.

Twenty-odd years ago, when I lived and worked in Japan, Macarthur and Deming were still both idolised and virtually deified there, and Deming is generally regarded as having more influence on Japanese industry than anyone not of Japanese parentage. One key principle which originated with Deming, and which is still utilised diligently by the Japanese to this day (the letters of which can be seen stamped on numerous documents, worksheets and presentation slides), is the process of Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA).

PEOPLE AND PLACES

In any Japanese office, regardless of the industry, the layout will nearly always be the same. Most important is the hierarchy and everyone’s status but, while deference and respect are important, there is not the obsequious subservience and sycophancy which Westerners mistakenly believe prevalent. In any of the engine companies, there will be several groups or departments in one large open-plan office. There will be, for example, one group – clustered around one desk or area – for, say, overseas market sales. Then there will be the same arrangement for overseas service, and for domestic sales etc. Engineering will usually have its own desk or area, as will product development.

Personnel-wise, there will usually be a row of desks across the width of the office, and at each desk is a General Manager (“Bucho”) overseeing each of the various departments detailed previously. The Bucho will sit with his back to the wall (or window) and gaze benevolently – like a school teacher – upon his staff in a row of desks in front of him. But the desks in front of the Bucho are at ninety-degree angles to his, so that he can look straight down and see nearly everyone’s face. Just imagine the letter “T” – the Bucho’s desk is the top bar while the pushed-together desks of his staff are the upright stalk.

The Bucho’s second-in-command – probably the true day-to-day boss – is the “Kacho”, and he (and it usually is a “he”, but it is changing) is the only person who sits with his back to the Bucho. This is because he will be at the head of the long row of tables overseeing his particular group. The Kacho’s 2IC, who is the acting Kacho when his boss is away on a business trip, is known as the “Kachodairi”.

While the Japanese are an orderly, polite and deferential people, it comes as a surprise to find that some offices can become very loud, boisterous and frenzied, as it is not unusual for Japanese on each side of a desk to carry on heated and animated conversations with those diagonally opposite, while someone may be shouting from the right-hand top side of the desk to someone at the left-hand bottom corner. It’s a hive of hectic, frenetic but constructive activity which is mesmerising to watch.

The above all works exceptionally well, and if you have a Yamaha, Suzuki, Tohatsu, Honda, Toyota, Nissan or Subaru, this is the environment in which it was sired. As to who really knows most about what goes on in the entire office, not just each division or department, it’s usually the OLs (Office Ladies). They pour the tea for the Buchos and see piles of highly confidential and sensitive documents (true!).

As for the actual manufacturing facilities (often separate and maybe kilometres away from the admin/office buildings), I have been fortunate to have visited two manufacturers’ factories: the old Suzuki plant in Toyokawa, the early Yamaha plant in Nippashi, and the latest, magnificently high-tech facility that Yamaha opened in Fukuroi within the last decade. Regarding the old plants, what came as an immense shock – primarily because habitable and commercial space is in seriously short supply in Japan – was where they were sited. Both of them were in old, suburban, semi-residential, areas, with the narrow access roads scything through small rice paddies (still in full use) about the size of the actual wicket-to-wicket playing area of a cricket field. The dichotomy was simply astonishing – the contrasting ways of old and new Japan simultaneously on show, coexisting in blended harmony.

One thing which still amuses and amazes me today is my recollection of the old Suzuki and Yamaha factories. For companies who are in essence sworn foes and aggressive, secretive competitors, the similarity of both plants was astounding – even to the location of a revolving circular test tank in each plant in which small motors were started and run. When each motor had done a full 360-degree rotation back to the tank operator, it had completely its timed test run. Looking back, I honestly thought the facilities so interchangeable that either brand could have been manufactured in either plant!

There is no doubt at all that today’s lightweight, sleek, compact 4 stroke outboards are what they are because of the BF35/45 series of Honda engines.

What Suzuki did was doubly outstanding. They created both the world’s first oil-injected outboard as well as a large, smooth-running inline 4-cylinder.

THE PRODUCTS

This is not a detailed study or a timeline of each brand and who invented what and when. Rather, it is about how and why Japan has been so successful and how the boating fraternity has benefited from companies which now set the rules and dictate, rather than emulate the trends. But as a refresher, there are four brands which are, in order of seniority: Tohatsu, Yamaha, Honda and Suzuki. Yes; this is chronologically correct – of the latter two, Honda preceded Suzuki with an outboard by one year (1964 vs. 1965), although the Honda was not really a true outboard in that it had a general-purpose engine that was coupled to, and able to be detached from, an outboard leg.

Heritage – particularly genealogy – is hugely important in Japan, and many products carry the family name of the founding father. With regard to the companies making outboards, the only one not bearing the founder’s name is Tohatsu, which is a contraction of Tokyo Hatsudoki (Tokyo Engine Company).

Of the four companies, the largest producer of outboards, by a huge margin, is Yamaha. Second place is hard to call (and may provoke enough heated discussion and argument to instigate a forum!), but there is probably little difference between Suzuki and Tohatsu. Worldwide, there is definitely a higher visible concentration of own-brand Suzukis than own-brand Tohatsus, but what must be borne in mind is the “invisible” Tohatsus supplied on an OEM basis to both Mercury and BRP.

Strangely, Honda, despite being the largest engine manufacturer in the world, is a distant last. Where the first three manufacturers each produce volumes well into six figures, Honda is simply not in that league, but (and I realise this is now becoming more convoluted and confusing so please bear with me!) Honda now supplies – also on an OEM basis – its 60-250hp motors to Tohatsu so that the latter manufacturer, whose 4-stroke line previously peaked at 50hp, now has a full range of 4-strokes. Interestingly, the 60- 250hp “Hondatsu” engines are not currently available in New Zealand. I will return to the Honda/Tohatsu association later, as I believe it will eventually be immensely significant.

In terms of overall numbers, then, the Japanese probably produce just over 600,000 outboard motors a year, with a total world market of about 850,000 units. As for US manufacturers, this leaves only Mercury (for whom Tohatsu makes most of the 2-strokes sold in the Oceania region and all their 4-strokes up to 30hp) and BRP. The only European outboard brand is Selva, most of whose 4-strokes are supplied on an OEM basis by Yamaha, anyway – so it can be seen how the Japanese forged ahead relentlessly and daringly to become leaders in a field in which they originally had no heritage and little experience.

WHY SO SUCCESSFUL?

Anyone who ever owned an early Datsun or Toyota would agree that, whilst those first efforts were rather inept and clumsy, the durability (of the engines, anyway) and the overall reliability were superb. It could also be seen that, with each generation, the overall concept became more cohesive, better executed and more appealing. The same paradigm transfers to Japanese outboards: initially worthy then becoming more dependable. Then, the product ranges began to mirror the Americans, followed by increasingly more sophistication – all finally culminating in inspirational engineering that assured world leadership.

In my earlier piece on Outboard Marine Corporation, I touched on their arrogant, blinkered refusal to accept that the Japanese would ever make a decent outboard – in fact, even up until the late 1970s, OMC in Europe was still convinced that the Japanese were blundering, dabbling dilettantes who were nothing to worry about and that the real threat would come from Volvo Penta (who subsequently exited the outboard business ignominiously in 1979). When it eventually became starkly clear to OMC that the Japanese were a genuine threat (something Mercury already knew), their pride and belligerence came churlishly and sullenly to the fore, mixed with a healthy dose of xenophobia. I remember attending an OMC service training course in the UK in 1979 and, to this day, still vividly recall the stick-on lapel badges handed out to all the attendees (and this is the actual wording): “Let’s nip the Nip in the bud, Bud.”

For Mercury, however, another motto (that of “If you can’t beat them…”) proved much more relevant. One example of OMC’s complete disdain for Japanese engineering was to scoff at the oil injection system, pioneered by Suzuki for marine use in 1980.

The GB30, first-ever Honda Outboard, 1964.

It had an engine-mounted reservoir and was an ingeniously reliable, effective (and essentially simple) gravity-fed system that guaranteed precise, accurate, metered oiling at all speeds. Mercury eventually realised that the future lay with such a system and enthusiastically incorporated their version of it (complete with Japanese Mikuni oil pump) on their first 3-cylinder loop-charged motors (the 70/80/90hp series) in 1987. But OMC did no such thing. They doggedly and stubbornly persisted with an overly complicated tank-in boat system whereby oil was drawn up from the tank by means of an extra chamber in the motor-mounted diaphragm fuel pump. However, In terms of miscibility, thickness and relatively “gelatinous” properties compared with gasoline, oil does not lend itself to being easily distributed by such a method and this system – VRO, for Variable Ratio Oiling (or Very Rarely Operating, as OMC staff quipped) – contributed hugely to OMC’s demise, but had they even possessed an ounce of pragmatism or humility (like Mercury), they could have eaten some humble pie and entered into an association with a company, like Mikuni or TK (or even Walbro in the US), that had experience in providing dependable oiling systems for 2-cycle engines.

One key reason why the Japanese succeeded so emphatically is that they regularly went out into the world to reconnoitre, investigate, research, replicate, make better and then constantly monitor. When early products failed (as with one particular engine on which the top mounts – direct copies of those on the old RD-series OMCs – delaminated disastrously in harsh commercial usage), it was commonplace for the parts to arrive swiftly followed almost immediately by an entourage of factory personnel who would do the work rather than leave it all to fledgling and uncertain distributors, some of whom had nervously parted company with established brands.

THE FUTURE

“Direct successor to the Yamaha P7A: a P125A from 1971. Still in use today in New Caledonia”.

As a rule, I contend that the Japanese are still not as effective at marketing as, say, the Americans or the Europeans – their overseas distributors/affiliates are, however, but they are usually run and staffed by locals. However, Yamaha is, and has always been, an exception to this, particularly when it comes to securing market share in less-developed nations. Yamaha has its own internal organisation to deal exclusively with such markets, but handling all products and not just outboards. People from this organisation – representing the sales, service, parts and product quality divisions respectively – are always in the field, working with smaller, less worldly-wise local distributors. If anyone has ever witnessed the stunning dominance of Yamaha in the South Pacific, in places like Fiji, the Solomon Islands, PNG and Samoa, now you know why.

In fact, in Fiji, the 2-stroke, commercial-spec Enduro 40hp is known as “The Hilux of the sea”. I will always remember the day, on the shoreline at Rakiraki in northern Viti Levu, Fiji, when I witnessed a commercial fisherman unclamping his Enduro 40 from the boat, hanging it on a stand and caressing it lovingly with a cloth – the way you would clean a bonnet ornament on a car. Now that’s brand loyalty! And, believe me, there is little chance of Yamaha losing its lustre, so the dominance will not dissipate any time soon.

Of the other main players, the second largest manufacturer of engines of all types (behind Honda) is Suzuki, which is a veritable colossus. In fact, when they first introduced 4-stroke outboards to the media in this region back in the late 1990s, they took great pains to reinforce the message that they were bigger than Mercury, Yamaha, Tohatsu and OMC combined. Indeed they were (and still are, even with OMC being supplanted by BRP/Rotax), but that was a simplistic, lowest common- denominator understatement – Suzuki is many, many times larger than all those companies put together. With the exception of a small range of commercial spec 2-strokes (to which they are reluctantly still committed), Suzuki is, I believe, the only company that could challenge Yamaha’s dominance in relation to a full range of 4-strokes worldwide. They started to build a second outboard plant some years ago (disturbingly close to one of Yamaha’s offices in Arai on Lake Hamana) but mothballed it once the GFC took hold. Should this second plant – right beside their magnificent new on water test centre – come to fruition, then the international dynamics of the entire outboard industry would change markedly.

After the 55A, Yamaha could do no wrong. It was the first large outboard to be made by the Japanese

As the worldwide market for outboards is relatively static, then any increased production by Suzuki would primarily steal market share from one other company: Yamaha. And Yamaha is acutely aware of this. Why Suzuki’s sales volumes are so low in a prime market like the US astounds me. With the products they have, they should be mixing it equally with Yamaha and Mercury in the US market, rather than scrapping with the three brands – Honda, Tohatsu and BRP – that pick up the leftovers. For my money (acknowledging that Yamaha’s no.1 position should be relatively unassailable for some time as they still sell a huge number of 2-strokes), Suzuki is the brand to watch. If they really had a mammoth, cohesively focused and sustained push for worldwide market share, there is no reason why they couldn’t knock Mercury from no.2 position in a relatively short time.

Tohatsu built their first outboard in 1956.

Now, to return to the Honda/Tohatsu tie-up on which we touched earlier. Honda truly set the outboard world on its end (and had all the major manufacturers greatly worried) close to 25 years ago, when they introduced the then-groundbreaking BF35/45hp (later BF40/50) series. These engines were slim, svelte and sleek and, at a paltry 88kg, weighed in at about the same as the 2-cylinder OMC 2-stroke 50hp of the same era – not to mention that they were the initiators of the flowing, rounded, no-sharp-edge styling now adopted by all outboard manufacturers. The BF35/45 was a daring, futuristic looking and fantastically presented product and it screamed innovation and quality. Honda then followed that with the first BF75/90 series which sold so stunningly well that the start-up and tooling costs were all amortized within one year.

After that, however, other than keeping up with trends and introducing catch-up models in horsepower categories in which competitors had already staked claims, their marine efforts began to taper off and became torpid. Honda is the classic case of the true “might-a-been” and it would seem that, once they proved the concept was realisable, they rapidly lost interest. I have always said that as far as the outboard business is concerned, Honda managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory…which brings us neatly to the possible ramifications of the joint venture with Tohatsu.

Next to Yamaha (although not in sheer production volumes, obviously), the brand most trusted by those who depend on an outboard to make a living is Tohatsu. Not dazzling, dynamic or boundary-pushing in the true sense, they have nonetheless had some quantifiable technological successes – firstly with their own low-pressure version (TLDI) of the Orbital direct-injection fuel system for 2-strokes (more dependable and less noisy than Mercury’s high-pressure interpretation). Also, they were the first to come out with a 25-30hp fuel-injected 4-stroke that did not need battery power to operate the fuel injection system – i.e. a true battery-less system which permitted, for the first time, fuel injection on a manual start engine. Latterly they have introduced a fuel injected 40/50hp 4-stroke which weighs in at around 90kg. However, until the recent tie-up with Honda, Tohatsu’s largest outboard was the TLDI 115hp.

This is where I am now prepared to make a bold, sweeping prediction (purely my own opinion and with no insight or insider knowledge of any sort). I believe, if one looks at current trends within Honda, such as their toying with concepts for high-output, small displacement, turbocharged automotive engines (Honda previously had no time for turbos and was an unshakeable advocate of “unforced”, normal aspiration) and their sortie into aviation with the frenzied development of a business jet, that they will eventually exit the marine market. If you knew Honda’s relatively paltry volume (they could afford to give every single outboard away free with a Civic or Accord and it wouldn’t even make a decimal-point error on their company balance sheet), you’d wonder why they’re still even in the industry. It is my belief (again, not based on any factual information whatsoever) that Honda’s outboard product line will eventually become the property of Tohatsu and that the oldest Japanese outboard manufacturer will then be part of a truly potent, formidable, unstoppable triumvirate. In the not-too distant future, then, an immensely potent four could become an all-powerful three.

Danny Casey is highly experienced, undoubtedly idiosyncratic, and immensely knowledgeable about things mechanical, new or old. His knowledge and passion are as a result of spending his whole life in or around anything power-driven – especially marine engines. His passion for boating is second to none, with his life a montage of fabulous memories from decades spent in or around water and boats, both here and in Europe. Danny has spent myriad years in the recreational marine industry in a varied career in which he has bamboozled colleagues and competitors alike with his well-honed insight.

His mellifluous Irish accent, however, has at times been known to become somewhat less intelligible in occasional attempts at deliberate vagueness or when trying to prevent others from proffering a counter-argument or even getting a word in. Frank and to-the-point, but with a heart of gold, it can be hard to convince Danny to put pen to paper to share his knowledge. Marine Business News is grateful that he took the time to share his thoughts and insight. Connect with Danny through LinkedIn.

To keep up to date with all marine industry news visit www.marinebusinessnews.com.au